As previous research has shown, public awareness of factual information on nanotechnologies (NT) is still at a low level in Europe and elsewhere. This means that citizens tend to build their perceptions and attitudes towards nanotechnologies upon ideological predispositions, personal values or cues from mass media. Media channels assume therefore a great responsibility in building opinions, creating familiarity with emerging technologies, and in involving the public in ongoing techno-scientific debates.

The Nanochannels project, that is funded under the 7th Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development of the European Commission, is an example of a concrete attempt to engage the general public in debating NANO by exploring a range of media channels.

The basis for the activities of the project – which include a press and media campaign for nanotechnologies (NT) awareness raising – was an empirical study on public opinion led by the Centre for Social Innovation (ZSI).

The aim of the empirical work was to explore how communication channels (including social media) can better target and inform the general public about NT related issues. One important focus of the research was to identify how people with a generally low interest in techno-scientific debates can be better reached and informed about new developments in NT (in the spirit of reducing knowledge gaps). At the same time, information and communication preferences and needs of those people who already have a certain stake in the NT debate, were looked at in comparison. An additional focus was laid on the role of social media and participatory approaches in engaging the public in the NT debate.

The empirical work, that was carried out in spring 2011 in several European countries and Israel, included focus group discussions with specific target groups (athletes, parents, retailers, and elderly), telephone interviews with experts engaged in NT communication, and a comprehensive online questionnaire in seven languages (English, German, Spanish, Italian, French, Romanian, Hebrew). The online questionnaire was answered by 1334 respondents from almost 50 countries. A representative sample for the lay public could not be achieved, so that the sample is biased toward the interested public in NT.

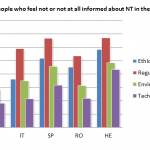

A first finding of the survey and the discussion groups was, that the general level of awareness of NT is considerably low across countries. Especially low turned out to be information that people have on regulations, policies, and governance of NT. The same may be said about ethical, social, environmental and safety aspects related to NT (see figure 1) . That stands in clear contrast to the main interests that lay persons expressed to have what regards NT, namely that they prefer to be informed on regulations, risks, and benefits of NT applications, rather than on technical knowledge.

A second observation was that there were hardly any people who considered NT to be generally bad or threatening. People were rather open to the new technology per se (or at least didn’t show a general rejection of NT), but had differentiated opinions on specific products and applications. It indeed created a state of uncertainty when people were informed that NT manufactured products already circulated in shops, but that those products didn’t have to be explicitly labelled as such. That shows us that awareness raising, without providing detailed information creates insecurity – a lesson to be considered in the science communication process.

At the same time, relatively high trust in national regulatory bodies mitigates the concern in NT manufactured products. Throughout all countries, products were considered to be trustful once they appeared in local stores, because it was assumed that they had run through sufficient national quality controls. Thus, in a first reaction, people didn’t necessarily see a need to get additional information on the products or the technology in order to protect themselves.

Not surprisingly, the participants were most critical when it came to products that are applied on the skin and body, and products that are used with children. Nevertheless, also here no general rejection was observed. A clear message was, however, that people want to be informed about the effects of products that we apply on our bodies and also on the reasons why we need NT in a specific product. There was also broad consensus throughout all participants in the survey that NT manufactured products should be labelled in some form.

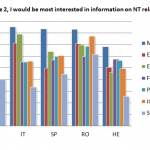

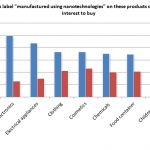

More evident than a general positive or negative attitude towards NT was the questioning of the actual usefulness of NT in the sense of: “do we need all that technology at all?”. So, the information that interested people in the first place was the extra benefit that they get when they buy nano – of course also under consideration of possible risks and impacts. The public’s interest in nano also depends heavily on the area of application (see figure 2). Highest were the expectations regarding the use of NT for products and applications in the area of health and medical treatment, and also for electronics. Medicine and health also proofed to be the area of application where public interest in and awareness of NT developments was highest. For products where the immediate importance of technological research was not so evident – like it is the case for children’s toys, food containers, or cosmetics – people tended to be more suspicious about the advantages of buying a NT manufactured product (see figure 3).

In the focus group discussions, the most debated controversies concerning NT products were of a more ethical or “philosophical” nature. A hotly debated question was if unequal access to new technologies creates uneven or unfair conditions and chances for individuals (as in the case of NT improved sports equipment), or if new technologies are gaining too much power over humans (for example that our bodies stop developing natural antibodies as a consequence of the antibacterial effects of some NT products). Of course also questions on more direct risks of NT products were raised, such as effects of nano creams for our skin or effects of nano coatings for the environment.

The majority of participants adopted a rather restrained position to the question if they would actively seek for information on NT once they got interested in certain products. People indeed recognize a certain obligation on the side of the consumer to get informed about new technologies and they would generally wish to understand them better – especially related to benefits and risks of applications and products. But in the end people are rather reluctant to get informed on NT, because the complexity of the issue discourages them to get involved. Older generation see it more as a duty of younger generations – who should be better prepared in school – to learn about new technologies that pave the way into the future (they are also the ones who dominate new information channels like the internet). Especially elderly don’t feel that they have a chance to catch up with the flood of new information, also because they are tied to conservative information channels. At the same time, youngsters don’t seem a lot more willing to invest extra time to research newest technological developments.

We found out that children and school curricula have a very good multipliers effect to spread information. Parents often get in touch with new information only because their children confront them with learning material or science projects from school. Public and live events (such as science exhibitions or street labs) also proofed to have a relatively high motivating effect for people to get in touch with new information and science (science to touch). In general it has to be said that there is a demand to make research processes more tangible, which means to rebuild trust by letting people participate in information on how technologies are researched, developed, and brought to markets.

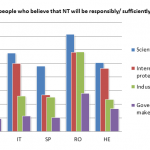

In a further step, we observed a rather restrained attitude what regards active participation of lay persons in the NT debate. Due to the lack of technical knowledge lay persons tend to prefer not to have a say or responsibility in techno-scientific decisions. At the same time, trust, that official bodies would sufficiently and responsibly regulate NT, is noticeably low across countries (see figure 4). A big question mark for the lay public is also how scientists should deal with uncertainties in science and how much autonomy should be given to research. At the end, it was only clear that positive and negative effects of NT should be investigated further and that some kind of regulatory body should guarantee that research did not go too far. A major threat to responsible decision making in NT was also continuously linked to a general distrust in independent science journalism and neutral information flows. Proposed solutions in the discussions with the public were a better scientific training for journalists, a communication training for scientists, or multi-stakeholder committees with members from politics, science, and civil society to ensure vertical exchange of knowledge.

Concerning the question where lay persons would look for information on new technologies like NT, the internet is clearly the first place to go (whereby people would rather consult Google or Wikipedia than scientific online journals or publications) (see figure 5) At the same time, the internet – and especially social media (here especially facebook) – are the information sources that are considered to be least trustworthy (even though we also observed a trust problem for popular print media and newspapers). News, science broadcasts and documentaries on TV are considered more reliable. Generally, penetration of NT issues in common media and information channels seems quite modest according to public opinion. The same is true for public events and museum exhibitions that deal with NT.

The future of engaging the public in science will lie in experiments with new and innovative communication channels, that include participatory elements and take up cultural attributes of the audience. What regards contents, it goes without saying that scientific developments have to be brought to lay persons in the form of stories that stand in connection with their immediate reality. How huge scientific breakthroughs are in the eyes of science are secondary to non scientists. In our research we identified three types of target groups for NT related information, whose motivation to get informed is sensitive on different drivers. The first group corresponds to people who see themselves as representatives of societal values and have general concerns about how far the technology should go (does NT make sense at all? Who has control over it? What about ethical, legal, social aspects? etc.) . The second group stands for the conscious consumer type who wants to have tools to weigh his/her buying decisions (what products and labels can I trust? what standardization processes exist? what are clear benefits and risks of specific products? etc.). For the third group the life long learning approach applies, in the sense that the self-responsible individual defends his/her position in the knowledge society (how can I stay on pulse of the time? How do I get the best overview over a new technology?).

A conclusion for science communication – that applies for all groups – is that there is a clear need for catching up with the diffusion of information on NT related to ethical, legal, social aspects. Another issue of vertical interest is information on the impact and risk assessment of NT that is being done on national, European and international level.